Here is an excerpt from Alaska Confidential. Thanks for reading.

Mister Manook was easily the most popular teacher at West Valley High School in Fairbanks. He taught Native Art. That means the artwork of the indigenous peoples of Alaska, who can most rudimentarily be separated into Indians and Eskimos.

The most common group native to interior Alaska, specifically the Tanana River and its tributaries, are Indians called Athabaskans. Further north near the ocean are the Eskimos, often called Inuit, a completely different ethnic group.

There are many groups of Indians associated with various regions of Alaska: the aforementioned Athabaskans, the Tsimshian, Eyak, Tlinket, Haida, and others.

The same goes for the Eskimos, the two major groups differentiating between Inupiaq and Yupiq.

As a quick disclaimer, if readers are offended by the terms Indian or Eskimo, I would like to offer you my sincere apologies, but only if you are one of these people.

There are a lot of terms that go in and out of vogue, and people who went to Berkley and have never met a Native Alaskan seem all too eager to tell you what you need to call these people.

I say Indian and Eskimo because that is what the people who I know, who I grew up with, usually prefer to be called and it’s what they call themselves.

The proudest Eskimo guy I knew growing up, essentially the Elijah Muhammed of Eskimos, had never heard the term Inuit until a tourist respectfully called him that, he was about nineteen at the time, and he laughed in the guy’s face.

So, I really mean no disrespect if you are a Native Alaskan, I’m just trying my best, and I have to make a decision on what words to use at some point, and if you’re a stuffy liberal with a thyroid problem, piss off, you don’t have any idea what you’re talking about.

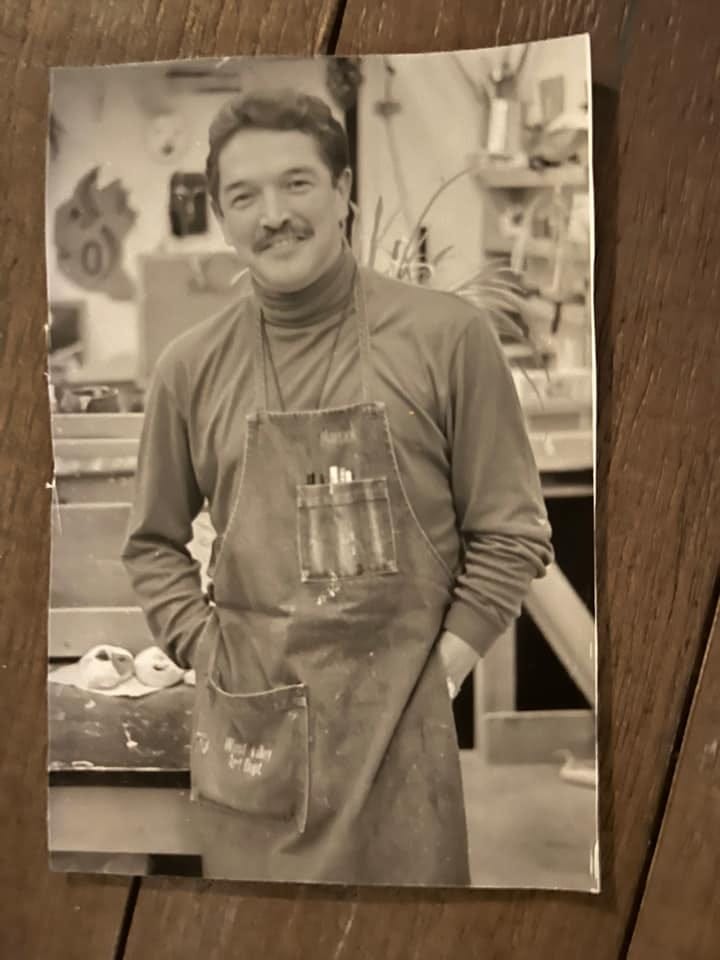

Mister Manook was an Athabaskan man, not too tall, barrel-chested, stocky, with rosy cheeks and a mischievous glint in his eyes. He was magnanimous, a butterfly constantly asking all the kids how this and that was going, jabbing them about their baggy jeans or suspect taste in music.

My friends didn’t have much respect for authority, certainly not as a default, but everyone respected Manook, and I learned to respect him on the first day I took his class.

Being aloof and generally unflinching in my desire to prove some unarticulated point and display a yet-to-be-determined grievance, I strolled into his class on the first day five minutes late, per my usual.

"What 'yer doin'?" Manook said to me with his village accent, which was fast and muddled, hitting the vowels hard, giving it an almost Shakespearian pentameter.

"Oh, hi, I'm in this class," I said, my slow drawl leading this sentence to take enough time for Manook to get a cup of water before I was finished.

"Why 'er you late?" he responded, matter of factly, holding eye contact.

"I don't know." In fact, I did know, I arrived to school on time and sat in the car listening to Bone Thugz-N-Harmony for fifteen minutes to be purposefully late out of principle.

"Well, leave. If you don't respect my class enough to come in on time then you can't be here."

This posed a huge problem for me. Throughout my high school career I attempted to spend as little time as possible in the classroom while still securing straight mostly A’s.

At our school, if you arrived to a class ten minutes late, even if you stayed, you were technically absent.

It was some byzantine system where something like five tardies equaled an absence, and you could have up to nine absences in a class, so if you paid attention to the logistics, you could never be on time for a class and your grade wouldn’t suffer.

When you missed a class, an automated call from the school would ring your house around dinner time and say, "This is to inform you that your son or daughter has missed one or more classes."

They didn't call your house if you were tardy though, so Manook telling me to leave and marking me absent put me in a compromising position with my mom, whom I was often on thin ice with by this point, and would flip out when these calls came in.

I would now have to remain home all evening diligently watching the phone, waiting for the robocall to come in, at which point I would answer it and say, "Yeah, Andy, you’re welcome, I can help you with your homework any time” to an empty line.

"Where am I supposed to go then?" I asked Manook.

"I don't give a damn," he said flatly.

Every other teacher would have sent me to the principal’s office or marked me late and allowed me to stay in the class. Manook handled his own business. He was his own authority. I wasn't tardy to his class again.

Manook's main focus was teaching us how to carve the traditional Inupiaq masks which were his focus of this general culture's art.

These were alluring works, carved tactfully from woods to form elaborate displays, often adorned with feathers and painted, representing exotic spirits and emotions and stories.

We were eventually going to be carving a cedar mask, which is an especially hard wood and takes substantial elbow grease and competence with various chisels, but we were to start with a soapstone mask, which is a soft stone that is relatively easy to mold, and could be done in a week or two.

Most of the students in the class had self respect and were eager to jump on their project. That was evident when we selected our soapstones to begin the process.

Most of the pieces were ten to twelve inches in diameter. I waited until everyone got their rocks out of a big carboard box and found what was likely a chip missing from one of them, smaller than a baseball card. I figured that this would take less effort to carve.

Everyone got to work, first filing their stone into a rough oval, and a few days later I had something the size of gumball machine toy and presented it to Manook. It was basically a ball with two or three holes drilled into it for the eyes and mouth, kind of a tiny snowman head made of rock.

"Is this done?" I asked, meaning, can I be done?

He looked at me with pity. "Sure," he said, shrugging his shoulders and tossing the trinket aside.

At the end of class Manook gave a brief lecture, mostly on the meaning of life, but also incorporating the theme that one particular student, a disrespectful gussak, or whiteboy, was a bad apple.

He stood at the front of the room, casually, with his spirits high, as if he were giving a toast at a Thanksgiving dinner.

"You kids, see, without effort, you're not going to amount to anything in life. You should do your best, every minute that you can. You're not going to have the advantages of other kids. Some of you will, but most of you won't. You're going to have to work twice as hard. Damn it, be proud of yourselves," he demanded.

He then launched into a dead-on impression of me - poor posture, mumbly, slack-jawed, emotionally vacant, "... Like, hey mannn, hey is this done bro? Is this done, this thing here? Why is this guy, this guy at this table right here, showing me this little piece of shit? Is that the way you want to be... What's his name again?"

My buddy Marty, seated at my table, spoke up. "Matt, he's, like, new here."

"Do you want to be like this guy, Matt?" Everyone shook their heads, and the bell rang.

The next morning, I decided to abandon my Sour Patch Kid sized mask and asked Manook if I could have a new rock, which he pretended to debate but then quickly accommodated.

I began working on it, but I was now behind in the schedule, and actually found myself coming in before school and on my lunch break to work in his shop, which was always open. He never locked it, even when he was away.

Most teachers would have returned to a thrashed room full of Taco Bell wrappers, a stolen stapler, and a bawdy diagram on the chalkboard, but Manook never worried, and he never had any problems even though his room was full of valuable tools.

A week later I did something which I am not sure I regret.

Many kids close with Manook knew that he had a fear of blood. Apparently, he had witnessed a stabbing in his village in his younger years, and now at the site of blood he would gasp, shriek, cower, and sprint out of the classroom with suddenly effeminate intensity. For another teacher a fear of blood wouldn't be a big deal, but Manook taught a class centered on carving, which involved sharp tools.

It was rare anyone would cut themselves. The basic rule of thumb was to cut downwards and away, which, if followed, makes an accident extremely rare.

If a kid came into class stoned, which was often, Manook could tell right away, and he’d quietly take them aside and tell them to leave and to come back tomorrow. No need to involve the school administration, which seemed to relish ruining a kid’s life for such an indiscretion.

Still, there was a rumor that there was a minor accident a few years back, and Manook didn't react well.

His classroom was an art shop, so, naturally I found some red paint. I asked a few of his most trusted, devout students if I should do it or not.

They seemed torn. On the one hand, it seemed potentially mean, but on the other hand, Manook was always mixing it up with all of us, playing practical jokes such as telling a particularly ambitious student that he was going to write a letter to Stanford telling them their masks sucked, and that they smelled.

One morning I took the paint and smeared it all over my palm under the worktable. I didn't want a Carrie scene, just enough to throw him off. I had it covering about half my hand and now running up my arm.

"Oh, damn,” I uttered. If he wasn’t talking, Manook’s class was dead silent, just the scratching of chisels on wood. In that split second, my nerves getting the best of me, I wanted to bail on the idea. But now half the class was expecting it and it was too late to back down.

So, when I broke the silence it didn’t come off as an emergency, I was trying to downplay it and move on from the situation as quickly as possible.

"What the heck is it?" Manook said, his eyes squinting at me curiously. I rose my arm out from under the table. He began to shake and turned his back for a split second. He then gathered himself and approached like one would an Ebola patient, asking from a good twenty feet away if he could see my hand.

"Jesus, you better..."

In an impromptu effort to disarm the tension I began to lick my hand like it was a popsicle.

Manook, heart racing, looked at me inquisitively, and the whole class began to break into laughter. He seemed annoyed, relieved, if not slightly amused.

"This guy,” he shook his head, “go clean yourself up man,” he said, stifling a grin.

Toward the end of class I was sitting there carving away with even more determination than usual, thinking this might compensate for my stupid shenanigans.

Suddenly I felt my spine tighten up and I couldn't breathe, in pure shock for a split second.

Manook didn't yell at me or report me for disrespecting him over my little stunt, he simply dumped an entire Big Gulp full of root beer over my head. Street justice.

At this point, he had earned my full respect. Alaskans tend to have affection for people who are rogue and unconventional.

Once he saw me waiting around the building after school because my mom was having car trouble and drove me home in his truck, which likely violated some condition of his employment. He asked me about my life, gauging, like he did with all of us, if we were okay.

It was nearing Christmas break, and I was slaving away on my new mask, making up for lost time. Before school, at lunch, after school, whenever I could get a minute.

Manook surely took notice, but never said anything about my mask, which was blossoming into something that resembled actual art.

One day he came over and stood over my shoulder and said, "It's lookin' real good," and I felt a rare sensation of pride. He did things like that, he knew how to build the suspense until his compliment would hit home.

That's the last thing I ever remember him saying to me because a few days later, just like that, he was gone. A brain aneurysm, some indiscriminate vestige of biology, took him out suddenly. He was forty-two years old.

The school was distraught, and the mourning period carried on throughout the end of the year, my last at the school, casting a pall over our otherwise celebratory mood.

The administration decided his class would be moved to another room and a personal friend of his, not another teacher, took over his current class.

We poked along, what was once enthralling was now just an uncomfortable exercise in completing our projects, so, just like any other art class.

We were told that we were allowed to go back into his now empty classroom and claim our things. The place was littered with dozens, maybe hundreds of masks, carvings, and paintings, but mine was nowhere to be found.

I wanted the mask back. I still had to put just a few finishing touches on it. Polish it.

I looked and looked on many different occasions, even after everything had been cleared out and picked through. I turned over shelves and couldn't find it anywhere.

There was no chance anyone would steal it or want it for any reason, so I wondered what happened to it.

On the last day of school I went back once more. I looked at Manook's black metal desk over in the corner. He used to keep his wallet in the top drawer. Everyone knew this, and nobody would even dare to think of opening this drawer, but now I would.

I opened the side drawers, littered with old paint brushes and scraps, already having been emptied out by friends or family. I opened his top drawer, the sliding drawer at the top of the desk, his wallet drawer, and there was my mask, straight in the center, looking right at me.

It could have ended up there for a multitude of reasons. He could have thrown it in there when one of the elders stopped by because it was embarrassing to him for all I know.

But I think that mask meant something special to Manook. I think it confirmed to him that he had made a difference in a kid's life. A kid who went from complaining, showing up late, and giving minimal effort, to a kid who’d stay after class to finish a project.

He could reach those who couldn’t be reached. He was a beautiful man. Of course he died young, that’s how that always seems to work.

Please subscribe or share. Thanks!

This is really beautiful. ❤️

the last assignment to get my degree at UAF was giving a presentation on Manook for the Native Art class there. I think these people go early so the rest of us can ride their spiritual wave. These deaths ignite something in us to go on.